|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Who's Dreaming Now?

(c) Morgan Thomas

Today it is almost a standard form

of approval to describe an artist's

work as 'provocative', 'subversive' or 'confronting'. A certain style

of

radicalism in art has come to be institutionalised as part of the everyday

currency of contemporary culture and criticism. Offering little in the

way

of resistance to the political or cultural structures which shape our

experience, this style of radicalism does not finally interfere with the

imperative of carrying on 'business as usual'. It seems able to live in

relatively peaceful co-existence with the mood of complacent conservatism,

or 'enterprising' self-interest, which has been in the ascendant in this

country for some time now.

In this context, what I find interesting

and even mysterious about the

work of Richard Bell is that it really is confronting. It is provocative.

To encounter it can be an unsettling and discomforting experience (let's

note the name of a recent show featuring Bell's work held at Fire-Works

Gallery in Brisbane late last year: 'Discomfort: Relationships within

Aboriginal Art').

What is it that gives Bell's work

its unusual political bite? It's

tempting to equate the confrontational character of the work with the

non-negotiable, 'out-there' political stance that it frequently seems

to be

advancing - and particularly to see this confrontation in terms of Bell's

liking for statements which he acknowledges are deliberately 'inflammatory'

in their formulation.

We might recall, for example, that

Bell is the Aboriginal artist who

proclaims: 'Aboriginal Art - it's a White Thing.' (This statement appears

as the subtitle to a recent essay by Bell entitled 'Bell's Theorem'; it

also forms the main text in Bell's Theorem, a painting from 2002.) We

could

note the patently incendiary - yet also cryptic and sometimes literally

encrypted - phrases like 'Kill Mabo' and 'Hide Ya Kidz' that Bell comes

up

with in some of his paintings. Or, in a rather different vein, we could

think of one part of the four-part work called Worth Exploring? (2002):

a

blown-up version of a carefully composed statutory declaration in which

Bell points out the illegality of the white occupation of Australia, taking

this illegality as the premise for the claim that everything subsequent

to

this occupation is ultra vires (illegal, outside the law), and drawing

the

consequence that all non-Aboriginal Australians must be counted as

criminals and all Aboriginal people recognised as the victims of crime.

We

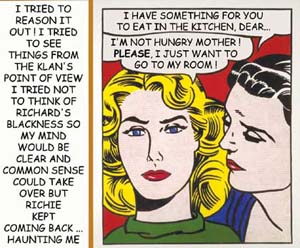

could also think of a new series of paintings, where Bell quotes from

the

comic-strip-style paintings of Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein to comment

on

attitudes to black-white sexual relationships, broaching what is a taboo

or

no-go area even now.

There is no doubt that the difficulty

of Bell's work, certainly for white

audiences, has a lot to do with the enjoyment Bell seems to take in coming

up with the most provocative formulations possible, along with his evident

lack of participation in talk of social cohesion and reconciliation. We

might well speak of a kind of ultra-Aboriginalism being voiced in Bell's

work, an ultra-Aboriginalism which is confronting precisely insofar as

it

lays down a law which refuses to accept or 'admit' a great many of those

(white) people who encounter it.

Thus, when I look at the statutory

declaration in Worth Exploring?, I

could say that it effectively situates me 'ultra vires' - outside the

law.

The text of the declaration makes it difficult for me to identify with

the

political and legal position that it articulates. At the same time, in

reading it, I am somehow put on the spot.

Something is going on here which

seems to take us beyond the obvious kinds

of provocation that I noted a moment ago, beyond the 'inflammatory' shock

tactics which Bell so often employs - important as those shock tactics

are.

We perhaps start to see how the very posture of intransigence that Bell

generally adopts in his work opens up the possibility of a radically

different kind of relationship with its audience, a radically different

form of communication.

In these more complicated terms,

Bell's work is confronting not so much

because of its resistance to, or refusal of, its audience, or a large

part

of its audience, but rather because of the way it brings that audience

face

to face with a resistance, a knot, at the very heart of the history of

black-white relations in Australia. From this point of view, the radicality

of Bell's work lies in the directness with which it addresses us. (Think

of

the title of a new essay by Bell: 'Wot chew gun ado?') If Bell again and

again forces us to encounter that 'difficulty' - that injustice, that

violence - at the basis of Australian history, it is surely because, for

Bell, without a recognition of this, there can be no relation, no

communication, no 'dialogue' whatsoever.

In this way the absolute and overriding

concern of Bell's work, the demand

for an Aboriginal justice, comes to imply an appeal to what we might call,

with or without Einsteinian overtones, a principle of relativity- that

is,

an appeal to a sense of human community and interrelatedness. With Bell,

the absolutism of the demand is intimately bound up with the relativity

of

the appeal: each supports and echoes the other. In Worth Exploring?, for

example, it is precisely in the name of 'civilisation' that Bell sets

down

his judgement concerning the criminality of the Europeans who colonised

Aboriginal lands - and of those who come after them and continue to profit

from this criminal act.

We begin to see that what distinguishes

Bell's work is not in fact some

blunt, full-frontal style of approach. In fact, in a strange way, we could

say that its capacity to confront us depends on a kind of balancing act

that it always involves, a certain elusiveness (rather like that of the

figures in his 'Shape Shifters' series) - there is a characteristic

reliance on a certain twist or series of twists.

We could think, for example, of Bell's

use of appropriation in the

confusingly named Untitled (1978), a work (in fact made in 2002) which

consists of two digital prints on canvas. This is a work which wears its

sources on its sleeve: the ghost gums and golden light leave no doubt

that

we're looking at one of Hans Heysen's pastoral idylls. At the same time,

when we see how the same Heysen image is replicated - and subtly altered

-

in both prints (one picking out yellow accents, the other picking out

pinks), we also know we're looking at something very like the work of

Australia's key exponent of appropriation art, Imants Tillers. And indeed

what Bell has done is to reproduce an untitled work made by Tillers in

1978

(hence the title) - a work which was by chance destroyed after it was

bought by the National Gallery of Australia.

What happens when Bell adds another

link to this chain of appropriation?

It's difficult not to see this work as making a satirical comment on the

way in which white Australian culture fetishises and appropriates the

dreaming (or marking) of land-ties in Aboriginal Desert painting. When

these panels were hung last year above a dining setting decked out with

Aboriginal designs and motifs, they looked like a lacerating riposte to

the

Desert paintings decorating the board rooms and lobbies of Australia's

corporate giants. It's as if Bell, in turn, has chosen to take a benevolent

interest in the colonial dreamscapes born of a white 'mythology' (just

as

Tillers' non-existent 'original' of this work is also now, partly thanks

to

Bell, the stuff of myth).

Yet Untitled (1978) might equally

be taken as calling on Heysen and

Tillers to add to the history of an Aboriginal painting, or dreaming,

of

the land, bringing them to attest to its endurance in the face of

colonisation, inviting them to be passing figures in this landscape. With

its problematic relationship to the Heysen tradition, the painting of

Albert Namatjira is then, perhaps, the real ghost haunting this work.

Bell engages in a different kind

of balancing act in Yam (2001), a

collaboration with the renowned Western Desert painter Michael Nelson

Jagamara.Interestingly, this collaboration arises from the fact that the

story of the yam extends across a great stretch of the Australian continent

- from Jagamara's country in Central Australia to Bell's in the east.

While

it may surprise us to see Bell painting in a seemingly traditional mode,

what's interesting is the way he inflects the large-format figuration

of

traditional motifs favoured by Jagamara in his recent work. In contrast

to

the bright colours which Jagamara generally uses, here the figure of the

yam is not differentiated by colour; the whole work is a monochrome,

painted in a sobre grey. Using a technique Bell frequently adopts in his

paintings, the yam-figure is formed out of gravel which is glued to the

surface of the canvas and then painted over. It is almost a figure in

relief, one that is not that easy to see unless you are looking at the

painting side-on or in certain kinds of lighting.

With its subdued, monochrome mode

of presentation, Bell's and Jagamara's

Yam refuses the European 'dream' of an Aboriginal art that is inoffensively

'spiritual' and decorative - it thus refuses the (white) mythological

creation of an Aboriginality that would fill up the void in Australian

identity rather than questioning it. At the same time, the yam which gives

this work its title seems to encapsulate the Aboriginal presence or voice

that Bell seeks out in his work. Like a real yam, this yam is a partly

concealed, subterranean presence - it is literally radical. In the way

it

buckles the surface of the picture and the way it branches out to fill

the

space, it is at once irruptive and almost infinitely extensive. Seen in

this light, this painting perhaps becomes, in an understated way, a

communication of the dream of Aboriginal justice and the desire for a

genuine 'civilisation' of Australian culture.

By now it should be clear that the

dreams we are thinking of here

intersect and collide. The difficult balancing act that Bell performs

in

his work traces their manifold connections - and at the same time puts

their relation in question. This is the radicality of his work - its appeal

and its demand.

Morgan Thomas

Brisbane, August 2003

Detail - Eddie 2003

for information about works, please contact Bellas Gallery - bellasgallery@ozemail.com.au